MIPS instruction Formats

An interesting facet of people is that we are quite adepts of thinking of new ways

of describing things. Once we do think of a new way of characterizing things that

then becomes a way of describing other things. In other words, we start to see things

through the lens of the new categorization system.

For years, computers were categorized by major groupings (RISC/CISC, 16-/32-bit,

Intel/Motorola). There instruction sets were characterized by functionality: arithmetic,

logic, shift, data movement, flow control, and so on. And then along came MIPS. MIPS

instructions are characterized bt their encoding; for example, R_type or I-type instructions.

Virtually all discussions of MIPS processors use the instruction format to categorize

instructions.

A few years ago, such a categorization would seem a strange as categorizing spending

by recoding the serial numbers of banknotes. Apart from some special cases such as

the Motorola 68000’s use of line-A and line-F instructions to categorize exception

types, no one ever thought about instruction encoding because it was some forma or

arbitrary instruction labeling carried out by the chip design. It was no more relevant

than the chassis number on the engine block in your automobile.

MIPS changed things. Instruction encoding that was once invisible, suddenly jumped

into the light. Why? Because the number of bits in an instruction is fixed and the

designer has to design the optimum bit-to-instruction mapping that maximizes the

professor’s power. The MIPS instruction encoding was an inspired piece of engineering.

Suppose the MIPS designers had taken a simplistic and naïve approach to instruction

set design. They could have argues something like. There are eight types of instruction,

so that’s 3 bits. Each instruction class can have up to 16 different members or variations,

and that’s another 4 bits. If we have three sets of 32 registers, there goes another

3 x 5 = 15 bits. So, far we’ve got through 3 + 4 + 15 = 22 bits. If we stop here,

we have 32 – 22 = 10 bits of a literal. That’s a tad disappointing.

MIPS uses a form of Huffman encoding which uses a variable length code; For example,

a Huffman code with four classes might be

Class 0 0xxxxxxxx

Class 1 01xxxxxxx

Class 2 001xxxxxx

Class 3 000xxxxxx

As you can see, each class has a unique prefix than can be rapidly decoded and the

rest of the bits can be used to define a specific instance of an instruction etc.

This approach allows us to use instructions with a short prefix as a means of providing

longer literals.

J-type Format

The MIPS encoding system identifies three major classes: R-type, I-type, and J-type.

Let’s begin with the J-type.

A J-type instruction divides the 32-bit op-code into a 6-bit code field and a 26-bit

literal field. The “J” indicates “jump” and this class is used for jumps. The six

most-significant bits of the J-type instruction are 000010 and the remaining 26 bits

are used to provide a 28-bit target address. The address is 28 bits rather than

26 bits because MIPS is byte addressed and all instruction fall on a …xxxx00 boundary.

The actual target address is obtained by appending two 0s to the literal and then

sign-extending the result to 32 bits.

Note that the J-type op-code 000011 represents a jump and link instruction. This

is the same as a jump except that the return address is saved in the link register.

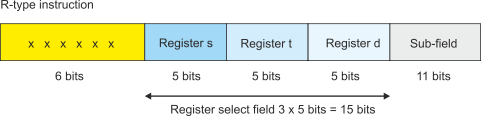

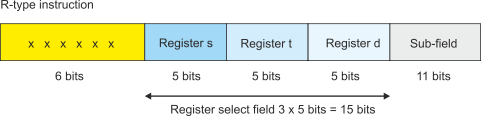

R-type Format

The workhorse of the MIPS instruction set is the R-format (here “R” indicates “Register”).

The R-format performs the reg0ster-to-register data-processing operations of the

MIPS.

In MIPS terminology, the three registers are designated rs (source), rt (source)

and rd (destination) and a typical operation is addu rs,rt,rd that adds [rd] ¬ [rs]

+ [rt]

The op-code is used in conjunction with the subfield in bits 0 to 10 to define the

specific operation and provide any parameters for classes of operation such as shift.

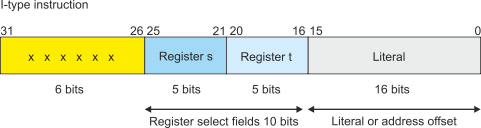

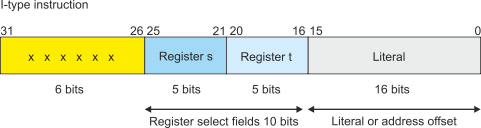

I_type Format

One of the most interesting formats is the I-type format where the “I” indicates

immediate; that is, the instruction carries a literal field. This is interesting

because, traditionally, CISC processors have regarded instructions will literals

as simply a variant of the parent operation; for example, add and add literal. MIPS

creates an I-type because of the encoding technique. One of the three registers is

sacrificed to the constant field and concatenated with the subfield as the following

figure demonstrates.

The I-type format implements three operations. First, there’s the typical register-to-register

operations with a 16-bit literal such as addu $4,$5,0x1234. Note that the literal

is a 16-bit value.

The next class of literal are the branch instructions such as bne $6,$2,target. Here

the branch performs a comparison between the two registers and executes a relative

branch to target if they are not equal. The target is a 16-bit offset that is extended

to 18 bits by adding 00 to the least-significant bits (remember all addresses are

on 4-byte word boundaries). Finally, the 18-bit offset is sign-extended to 32 bits

and added to the program counter, PC to give a relative offset.

The third member of the I-type class is the load and store instructions because these

use a pointer register, a source or destination, and a literal offset; for example,

lw $t1,0x1234($at)copies the 32-bit value at memory address [$at] + 0x1234 and puts

the result in register $t1. Note that the offset is a 16-bit value sign-extended

to 32 bits.

This list is not exhaustive. There are special instructions such as coprocessor instructions

that perform operations on co-processors. The coprocessor instructions have the op-code

0100xx, where xx, describes four options. The remaining 26 bits are divided into

5,5,5,5,6 bit fields to define coprocessor registers and pass details of the operation

to be performed.